| Why Africa?

From America to Africa and into the Wild

I was born wanting to go to Africa.

Why, it's hard to say—the call of the primal, an affinity with cats, the lure of undiscovered country, the danger, the forbidden, the face of death. The desire became a quest on a train bound, of all places, from Shanghai to Beijing in 1987. I sat with friends, urging them to make my desire theirs. No one was willing.

My husband and I scheduled a safari with his brother and wife, Rod and Toni Burgoyne, to Botswana, Zimbabwe, and South Africa in April 1997. Six weeks before our departure, our beloved cat was diagnosed with lymphoma. We canceled our trip—now my brother-in-law won't travel with us—and administered chemotherapy to our dear Tess. She died of kidney failure in June. She had been my only cat. We buried her in the backyard and rescheduled our "wings" trip in August.

There's only one flight a day from New York to Johannesburg, leaving at 6:20 p.m. on South African Airways. We managed to survive the fourteen-and-a-half-hour flight, checking into a typical Holiday Inn. The next morning we stored our excess luggage in the Johannesburg Airport, taking only twenty-five pounds of baggage into Botswana, including camera equipment—a challenge, especially for this female.

We flew to Maun, cleared customs, separated ourselves from those tourists carrying guns, and met our first bush pilot—a twenty-three year old. If that thought wasn't scary, his thirty-year-old, single-engine Cessna was. I admit, I felt like Karen Blixen, flying low over Africa's vast wilderness. Below were nothing but baked brown earth, dried-up riverbeds, and bush fires blazing out of control, sending up smoke signals.

I saw only one animal from the air—an elephant, who seemed not so threatening compared to the Cessna. I still hear the roaring clamor of its engine, the rickety jiggle of the cockpit panel. Another Cessna outside the pilot's window, and suddenly we

|

were in a drag race to the finish—a dirt runway near Savuti. We won. Phineas, our guide, was waiting in a four-wheel open Land Rover. Already, I felt exposed, breathless, anticipating three weeks of safaris ahead of us.

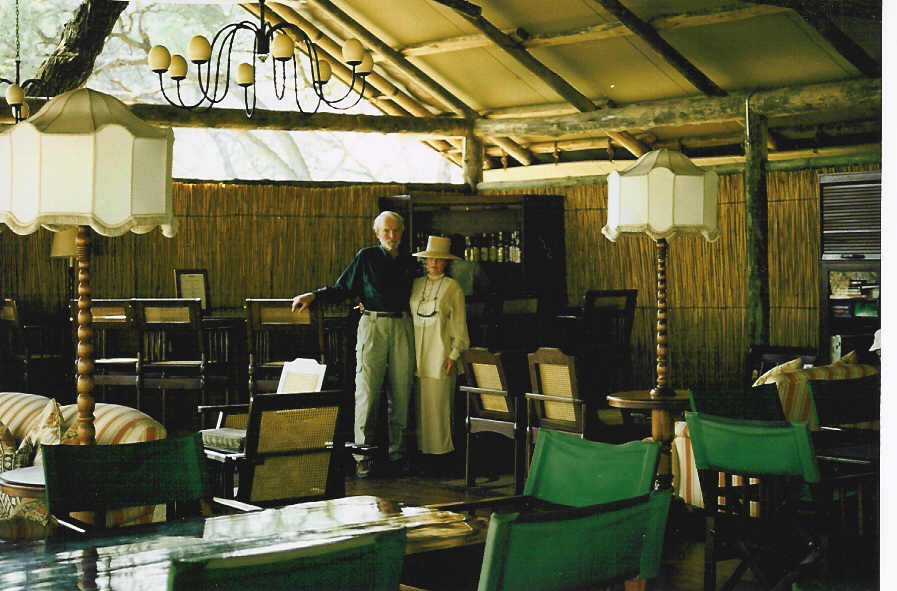

Our first camp was luxurious: twin beds with mosquito netting, custom-made sisal carpeting with hand-painted ethnic designs, double washbasins, a shower as big as a walk-in closet. The furniture had been built in Zimbabwe of local kiaat timber. We weren't exactly roughing it, not with hot water, hair dryers, and same-day laundry service, a necessity considering the few clothes we had. We learned later the camp was run by Orient Express Hotels. That night, we dined in our first open-air boma, the hosts serving a dinner fit for royalty.

Later, by the campfire, the Cimmerian night, without lights from any city nearby, touched the sand. I felt a chill. In this hemisphere, the sky turned on itself; Scorpius had overthrown Orion. We were told we could not walk back to our tent unaccompanied by a guide. "Hyenas," Phineas said, "come into camp this late," and I knew

only few men go

flaming, forbidden into

the Okavango.

|